This started out as a list of written pieces I’m studying to learn to write well.

But as I gathered better and better material, it morphed into “the guide I would have written to my younger self to learn to write properly”.

Must-reads

You might think the must-reads would cover the craft of writing – but they’re not. Instead they cover what to write about and why.

To make the most of this guide, you should go deep in these ‘must reads’. Really contemplate these lessons. Let ‘em marinate until they’re second nature.

Leadership Lab: The Craft of Writing Effectively, Larry McEnerney.

This entire video is required viewing for anyone who writes. Your highest priority at all times is that your writing is perceived to be valuable.

There’s a lot of gems in that talk: models of knowledge, reasons why we don’t write well by default, and so on. But the key takeaway is how to create the perception of value.

Larry’s talk is best when followed with a chaser of several of Paul Graham’s essays. You’ll notice that Paul echoes the “valuable” theme. Which is no coincidence because he spent the last couple decades thinking about startups.

General and Surprising, Paul Graham.

Paul defines the most valuable insight: one that is both general and surprising. Most of the ideas you’ll come up with are either or neither, but not both. Paul’s heuristic will extract those ideas that are actually worth writing about.

Paul shares an easy trick to get moderately valuable insights: start with a general xor surprising insight, and add small amounts of whatever is missing, either generality or novelty 1.

It should be clear to you that there are far more moderately valuable insights than greatly valuable ones.

Which means that (a) it’s easier to find the former, and (b) Paul’s trick is quite useful to quickly do so.

Why Smart People Have Bad Ideas, Paul Graham.

In 2005, Paul and his colleagues sifted through the applications for the first Y Combinator batch. At first, they divided each application into two piles: promising and unpromising.

But then they noticed that they needed a 3rd pile for promising people with unpromising ideas. In other words, highly competent people who submitted bad ideas.

Here’s a stab at projecting Paul’s points onto writing. In other words ‘how to avoid bad writing topics’:

- write something people want to read

- don’t just plunge into the first topic that you think of; ideation is quick, writing is slow

- valuable ideas are not necessarily cool / fun

The Age of the Essay, Paul Graham.

This is an essay that teaches you how to fix your writing if it was broken by the K-12 public education system.

Writing, Briefly, Paul Graham.

Some points that resonated:

- use anaphora to knit sentences together

- publish stuff online, because an audience makes you write more, and thus generate more ideas

- print out drafts instead of just looking at them on the screen

- learn to distinguish surprises from digressions

- learn to recognize the approach of an ending, and when one appears, grab it

A momentary digression: The phrase “knitting sentences together” seemed like a throwaway to me. At first. But its proximity to the word “anaphora” is a sign that there’s something deeper here. I couldn’t reconcile the exact meaning of these two concepts in relation to each others, so I dug deeper. It turns out there’s an entire field of English that I wasn’t exposed to in school or afterward. I wrote up some notes on starting points for subjects related to anaphora and flow.

LOL “recognize the approach of an ending”. This a thousand times. Endings are hard. Catch one while you can.

Structure

This section and the following sections delve further into the ‘how’ of writing.

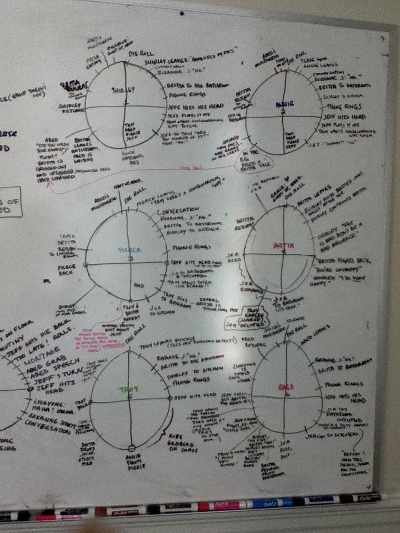

Dan Harmon’s writing series on Channel 101

A great intro to the ‘monomyth’ story structure: Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit, 102: Pure, Boring Theory, 103: Let’s Simplify Before Moving On, 104: The Juicy Details, 105: How TV is Different, 106: Five Minute Plots. Dan explains the well-trod Joseph Campbell material without any clumsy fumbling with spirituality.

If you’re a Ghosty member, check out this gallery of real examples from Community. You can see how the story beats line up to the Dan’s four-quadrant model.

Structure, John McPhee

How to write about something personal, specific, and technical - yet still make it interesting. (The bits about Kedit and writing software are also fascinating.)

Meta-writing

“Why’s this so good?” No. 16: David Foster Wallace on the vagaries of cruising, Megan Garber.

This critique is just perfect. I would quote the whole thing here if there were space. There’s a master class in just two paragraphs of the intro:

Shown Not Told, Onion-Peeled, Sublimated

all the little ironies and oddities

a metaphor – for death, for life, for capitalism, for colonialism, for America

on the one hand a travelogue with a transformative narrative arc and appropriately Dickensian details…and on the other a cultural critique of the m.v. Zenith, its curiosities, its context, and the various Global Phenomena it represents: economic entitlement, imperative leisure, people who use “cruise” as a verb

I mean…damn. If that doesn’t skewer every bit of magazine-y writing you’ve ever read…

I love the intro to Megan’s piece because it just casually deconstructs these styles that many newbie writers inevitably admire and eventually try on for size and discard as they find their own style. Save yourself time - de-mystify those styles for yourself early on to move past them quicker.

Great works

This next collection of works indirectly teach how to write well. They’re great works in and of themselves; intended to be enjoyed, studied, and deconstructed.

Fan Is A Tool-Using Animal, Maciej Ceglowski. How to write about a personal, specific experience while making it about everyone but yourself.

Fans improve our culture. They analyze content, pick it apart and create new versions.

Shut up and listen- ask people what they want. They can’t wait to tell you about their needs.

Meditations on Moloch & Misperceptions on Moloch, Scott Alexander. How to write about the engine at the heart of the problems with our world.

A Big Little Idea Called Legibility, Venkatesh Rao & Book Review: Seeing Like a State, Scott Alexander. How to write about paradigms at a global, macro level.

Utopian for Beginners, Joshua Foer. If true, this is either the most fictional-sounding non-fictional story, or the most non-fictional sounding fictional story.

Resources

Nieman Storyboard. This entire site is a rich resource, but I’m most drawn to two of its ongoing series:

- Why’s This So Good?, analysis of what makes pieces so good

- Annotation Tuesday!, annotated notes on real pieces

The Best Magazine Articles Ever

Footnotes

-

An example of this principle is my essay What your most hated feature can teach you, which I wrote before I knew about the ‘general & surprising’ model. I started with something (somewhat) surprising and (very) specific: the insert key is not useless, and then generalized it by talking about what this insight says about our relationship to our tools. I could have gone the other way instead: taking an insight about how we view our tools, then adding the story about the insert key. Now that I’m looking at it through the ‘general & surprising’ lens, the latter approach might have been more interesting. The insert key anecdote is super-interesting (to me, at least!), but there are probably a handful of much more surprising demonstrations of the general insight. ↩